Context

`

`

Now that the Chicago conference is in the background and with the NATO supply lines still suspended, the question is what’s next in the US-Pakistan ties. The statements from Leon Panetta and General Dempsey this week revealed that there was no change in the original position of the US, or in other words there has been little progress as far as Pakistan’s interests are concerned.

With all the talk of reconciliation in Afghanistan, the emphasis remains on a military solution. The drone strikes continue and so does the pressure on Pakistan to take on the Haqqani network. On the other hand, civilian casualties in Afghanistan also persist, and Karzai had to dash back from another foreign trip.

Under such circumstances, General Dempsey’s assessment is correct: with no progress on the reconciliation process with the Taliban, NATO’s transition is in danger. On the other hand, how does one interpret Panetta’s statement that US is losing patience with Pakistan.

Analysis

Timing

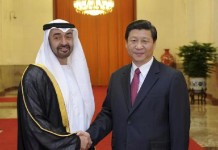

The first thing to consider is the timing of the remark, delivered in Afghanistan. Panetta arrived there after attending the Shangri-La security dialogue and visiting India. When the US Secretary of Defense reached Kabul, Karzai was on a visit to China attending the SCO conference. At the gathering, Afghanistan’s membership was upgraded to an observer status, the same membership level as Pakistan, Iran and India.

Secondly, while Panetta was in Afghanistan, media was reporting on NATO’s involvement in yet another spate of deadly attacks involving civilians, with backlash expected from Afghans. In such an atmosphere, the coalition forces usually attempt to redirect Afghan anger towards Pakistan, as the country remains deeply unpopular in Afghanistan. This by no means is to suggest that there are no serious challenges in US-Pakistan ties over the state of Afghanistan conflict.

Threat Perceptions

The comments also point to American irritation with the state of affairs in the AfPak and for its inability to convince Pakistan and its army to move in to North Waziristan, where Al-Qaeda No 2 Abu Yahya Al-Libi was reportedly killed in a drone strike on 4 June. The question is, in the aftermath of the Salala incident and the closure of NATO supply lines, what can follow. There is obviously an increase in drone strikes with a possibility of more boots on the ground-style operations that could lead to another incident.

Up to this point, Pakistan has prevented many of the recent interventions to escalate in to a confrontation, being cognizant of the vast gap between the military capabilities of the two countries. It did so by keeping the information on both the Salala and Osama operation vague. Both incidents went on for more than an hour, providing ample response time. Similarly, Pakistan has officially kept quiet about what it can do to counter drones.

Technically, when one gets in to the realm of what can be done to counter drones, one is inadvertently talking about an unfriendly state. However, US and Pakistan do not yet consider each other an adversary. Nonetheless, what happened at Salala may have altered Pakistan’s posture, making any future untoward development extremely hazardous. Both Pakistan and US understand the worst thing that can happen to the army of any country is for it to loose morale. Therefore, they cannot allow their forces to be attacked and not do anything about it for long.

There is a third element to NATO and American frustration, probably the most important one, involving a change in the balance of power in South Asia. This in turn is dependent on Pakistan’s acquiescence and a transformation in its traditional security paradigm. In recent months, speedy movement has been seen in country’s attempts to improve ties with India and to connect itself with the larger regional trade and economic prospects. However, this has not resulted in a swift action against the good militants and Taliban, as US and India would have wanted.

Good and Bad Taliban

The US wants Pakistan to take on all jihadists and militants irrespective of their good and bad character, while Pakistan considers the good militants insurance against India as well as other potential adversaries. At the same time, it is also true that if the region were economically prospering, there would be no need for such hedging. The reality is that the economic benefits are in the future while the security threats are to be dealt with now.

Moreover, keeping the Middle East situation in mind, the religiously oriented and nationalist groups are playing a prominent role in the dynamics that are emerging from the Arab revolts in places like Egypt, Syria and Libya. From the perspective of Pakistan, it is perhaps the most critical time to remain engaged and maintain influence over groups that are friendly towards the state.

The key challenge for US to not take Pakistan fully on board over Afghanistan is because of the distinction it makes between good and bad Islamic militants. Getting on board on American terms would translate in to many new enemies for Pakistan that can possibly unite against it at some point. On the other hand, US understands the lethality of these groups; the demise of Soviet Union would have been impossible without them.

This divergence of strategic interests needs constant work, most importantly requiring patience and compromise. In the end, every country has to be loyal to its interests, but diplomacy is about bridging the differences. As opposed to classifying the factions based on if they affiliate with Al-Qaeda or not, it should be changed to groups that can be controlled. The question of who controls the groups that are controllable will require yet another bargain. And obviously, with control comes accountability.