By Dr. Syed Mohammad Ali

Context

While longstanding, relations between the US and Pakistan have experienced much turbulence especially since 9/11. It looks like the unceremonious American exit after two decades of intervention in Afghanistan is going to become another source of contention for this troubled bilateral relationship. Yet, some opportunities still exist for the US and Pakistan to cooperate, especially with regards to ensuring long-term stabilization in Afghanistan.

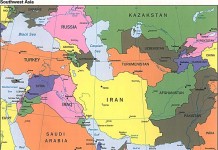

The story of Pakistan working with Saudi Arabia and the US to help wage a holy war against the Soviets in the 80s is well known. But Pakistan’s security cooperation with US goes back much earlier. Pakistan joined Cold War alliances like the Baghdad Pact in 1955 and the Central Treaty Alliance in 1959. In 1958, Dwight D. Eisenhower even requested Pakistan’s Prime Minister Feroze Khan Noon for a secret facility, to fly reconnaissance flights over the Soviet Union. This arrangement was only uncovered when an American U2 spy plane which flew from Peshawar was shot down in May 1960 by Soviet forces.

In the Global War Against Terror (GWOT), Pakistan was pressured to become a ‘frontline’ state, and to help the US fight the same hardliners it helped create in Afghanistan during the 1980s. Pakistan has repeatedly complained of being embroiled in GWOT and not being adequately appreciated for its cooperation and sacrifices. On the other hand, the US has long suspected Pakistan of being duplicitous and not doing enough to ensure stabilization in Afghanistan.

It took the US almost twenty years to realize that there is no military solution to the Afghan crisis. While American talks with the Taliban have produced lackluster results, these ‘peace’ talks did allow President Trump an opportunity to announce a US military withdrawal. Once the withdrawal decision was made, it has proven very difficult for the incoming Biden administration to reverse course, despite his claims of wanting a ‘responsible exit’.

The US and other NATO allies will probably continue proving financial assistance to Afghanistan for the foreseeable future, including funds to the national army that they created. While the US is withdrawing militarily, the budget request for the next fiscal year is still asking Congress for $3.3bn to support and sustain the Afghan Security Forces, a jump of 9.2 percent from 2021. In addition, the US intends to keep ‘over the horizon’ counter terrorism capabilities in neighboring countries to ensure that ISIS and Al Qaeda are not able to gain enough ground in Afghanistan that they become an international threat again.

Pakistan would logistically have been an ideal base for US counter-terrorism operations, but the Pakistani government has categorically rejected the possibility of such cooperation. Pakistan’s refusal to give the US military bases to undertake operations in Afghanistan is understandable. Such a move would be deeply unpopular given the controversy surrounding tacit Pakistani endorsement of US drone strikes despite the collateral damage caused by them. It may risk fueling extremist attacks within Pakistan, and it may irk the Taliban who have warned neighboring countries of hosting an American military presence.

Media reports reflect that under the Biden administration budget request for fiscal year 2022, some military training and economic assistance for Pakistan is forthcoming, but the overall suspension of military aid that came about in May 2018 remains intact. What will be the actual size of US aid to Pakistan next year, especially if it does not succumb to American pressure to provide it military bases to operate in Afghanistan remains to be seen. Pakistan could be pressured by the US via lending agencies like the IMF. Threatening to blacklist Pakistan using the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) if it refuses to allow the US to operate military bases on its soil would not be fair. But in the realpolitik world, states can often resort to such tactics to try and get what they need.

Emerging Complications and Compulsions

While Pakistan keeps insisting that it is open to any permutation of power sharing which are acceptable to the Afghans, the nation is widely suspected of preferring a hardline Afghan state which would rebuff Indian attempts to encircle Pakistan. The latest Congressional Research Service Report’s assessment of Islamabad’s motives are not too rosy. It concludes that Pakistan will prefer a weak and destabilized Afghanistan, instead of a strong Pashtun-dominated government (which would continue to resist the status of the Durand Line and appeal to Pakistan’s own restive Pashtun minority). Such suspicions are questionable, however, given that destabilization in Afghanistan would incur the hefty cost of another large wave of Afghan refugees pouring into Pakistan. Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions when it comes to ensuring a semblance of order and stability in Afghanistan. The Tajiks will probably continue to resist the Taliban’s attempt to gain complete power over the country, and they will again look towards different regional backers to challenge the Taliban. Turkey’s recent offer to take a lead role in ensuring the security of Kabul airport after the American departure is an interesting twist in this regard, hinting at an expanded Turkish role in Afghanistan in the foreseeable future.

US attempts to support the Afghan national army from being overrun by the Taliban may compel the Taliban to increasingly rely on Al Qaeda’s support. The CIA has also built-up counter-terrorism militias over these past several years, which have problematic human rights records, and these militias may now back varied factions motivated by personal gains. The presence of major illicit arms and drug trade cartels operating in the region could add to the threat of worsening violence.

While Pakistan can play an important role in helping create stability and economic prosperity in Afghanistan, the US continues to view Pakistan from the narrow lens of achieving its own counter-terrorism goals. Pakistan has not done much either to provide alternative pathways to working with the US which could help improve the lives of ordinary people in Afghanistan.

While Pakistan can play an important role in helping create stability and economic prosperity in Afghanistan, the US continues to view Pakistan from the narrow lens of achieving its own counter-terrorism goals. Pakistan has not done much either to provide alternative pathways to working with the US which could help improve the lives of ordinary people in Afghanistan.

The Way Forward

Recent Pakistani attempts to reboot relations with the US are perhaps too ambitious given US suspicion of China, and the Biden administration’s decision to continue working with India to contain Chinese influence. Instead, Pakistan now needs to focus on more pragmatic and mutually beneficial opportunities for collaboration, such as the need to enable much needed stabilization in Afghanistan.

One possibility in this regard is the activation of the much discussed but still not operationalized reconstruction opportunity zone (ROZ) on both sides of the Durand Line, via which jointly produced Afghan and Pakistani products could be given preferential access to US markets. A well-functioning ROZ could create a strong incentive for Pakistan and Afghanistan to cooperate and it could provide the means for boosting economic sustainability within Afghanistan.

There is ample room for the US and Pakistan to work together to avert escalating chaos in Afghanistan. In his June 21 article in the Washington Post, Prime Minister Khan reiterated his desire to be a willing partner for ensuring peace in conflict-ridden Afghanistan, even though his government is unwilling to host US military bases. He also significantly asserted that Pakistan would reject attempts to impose a government in Kabul though the use of force.

The need for promoting economic connectivity and regional trade to promote lasting peace and security in Afghanistan is well recognized. Within this context, an ROZ between Pakistan and Afghanistan is an idea whose time has come. There is need to show pro-activeness in articulating parameters of such an ROZ, so that needed incentives are in place for boosting economic cooperation between the neighboring states as soon as a power-sharing formula emerges in post-withdrawal Afghanistan.