Context

By Kulsoom Belal

This article is part of PoliTact’s recently launched initiative to look at the events of the Pacific region from the vantage point of South Asia. In order to do this, one has to also study where South Asia belongs in the larger strategy of major international powers. Under this theme, various political, security and economic implications of the events of the wider region will be explored.

At one level, there is a need to understand how the recently announced China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) fits in the larger Chinese One Belt One Road (OBOR) vision. Since the announcement of OBOR strategy, a considerable number of countries, around 65, have signed up already.

At another level, there is the question of how OBOR and CPEC compare to the American New Silk Road architecture for South and Central Asia and the Indian ‘Act East’ and ‘Connect Central Asia’ policy. Then there is the US-India ‘Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia Pacific and the Indian Ocean’ that is exploring the leverage offered by connecting the Indo-Pacific region with the Asia-Pacific, such as through the associated Indo-Pacific Economic Corridor (IPEC).

In this context, a number of questions are raised, are these different visions complementary or contradictory. Moreover, what would the US and Chinese strategic considerations mean for South Asia in good and bad case scenarios.

Equally important is the distinction between land and sea access. A Chinese White Paper released in May highlights its military strategy and has added emphasis on access and protection of sea routes. The paper states, “the traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned.” The document adds that China will develop “a modern maritime military force structure commensurate with its national security and development interests [and] safeguard its national sovereignty and maritime rights and interests.”

Both US and China have publicly claimed these are complementary visions. For example, in South and Central Asia, US is promoting interoperability by helping to streamline customs, transit, and taxation policies of various states and this will certainly help the Chinese. However, US is faced with its own strategic imperatives as it implements the Pivot to Asia strategy. If it allows the present trajectory of China, it could reconfigure the balance of power in the region in a way that may not be favorable towards the US.

Then there is the question of how Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are likely to play out in contrast to what BRICS is attempting to shape via institutions like Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). These are immensely intricate agreements, but are seen as giving advantage to one or the other player.

Moreover, in July India and Pakistan both have acquired full membership of the China and Russian dominated SCO, which has added another layer of complexity to the ongoing economic and security balancing act in the region.

In retrospect, the shape of present day trade and economic corridors were largely shaped by geographical proximity, historical linkages, and political realties. As a rising power with energy needs, China intends to realign them in its favor. And when one does that, it has the potential to unveil immense economic opportunities and security risks that previously did not exist.

In a series of articles we will discern, synthesize and interpret the above laid out dynamics. In part one, the attempt is to understand the OBOR vision and how CPEC fits in it.

ANALYSIS

China’s One Belt One Road Vision

When laying out the master plan for OBOR, China must be grappling with two strategic considerations. One, what would a potential future conflict with US, or more generally with the West, mean for its security and economic interests. Second, how it would secure the energy needs if the strategic sea pathways, through which much of its present day trade passes, were to become unstable. These worries are not unique to China alone, every major international actor is attempting to find their respective answers to these growing risks.

In view of these strategic considerations, China’s OBOR and its various tributaries, appear to provide alternative routes for the sustenance of its trade and the steady supply of energy needs to maintain its growth.

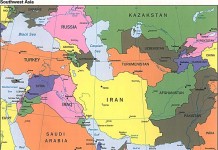

OBOR is a combination of two routes; the New Silk Road Economic Belt will run westward overland through Central Asia and onward to Europe. The second route, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR), will run south and westward through sea to Europe, with stops in South East Asia, South Asia and Africa.

Under the auspices of OBOR, at least six arteries are being developed, with CPEC being one of them:

1. The China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor will be built with China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region as its starting point

2. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) will be built to connect the ports of Pakistan’s Gwadar with Xinjiang’s Kashi

3. The northern China-Mongolia-Russia Land Corridor will connect Russia to China and starts from the Chinese province of Heilongjiang, and

4. The south running China-India-Bangladesh-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM), will be built with Kolkata as its starting point

4. The south running China-India-Bangladesh-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM), will be built with Kolkata as its starting point

5. The Indochina Peninsula Corridor

6. The New Eurasian Land Bridge, running from central China to Europe via Kazakhstan, Russia and Belarus

OBOR will allow China to consolidate its access to Eurasia, Central Asia, South East and East Asia, including Africa. More significantly, it will help its penetration in to the maritime regions, especially the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Sea. These regions are estimated to include 4.4 billion people, constituting 63 percent of the world population, and US $2.1 trillion in gross production that makes up 29 % of the world GDP.

China’s trade with the US and the Western Europe, its traditional markets, has seemed to stagnate. Considering this, OBOR will provide lucrative opportunities for China, expanding its trade with the littoral and inland states. According to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, China’s bilateral trade with countries along the Silk Road aggregated to 26 percent of China’s total in the first quarter of 2015.

CPEC in Relation To China’s One Belt One Road

Thus, it is clear that while CPEC is just one of the tributaries of the Chinese OBOR vision, it is perhaps the most important one. Ideally, China would desire all of the corridors to operate as envisioned. However, the success of each strategic passage is dependent on mitigating several key security risks.

The Gwadar Port situated very close to the Strait of Hormuz, will allow China the shortest access to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. Moreover, it will provide an alternative route to the conflict  prone and crowded Malacca Strait, sandwiched between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. Obviously this carries economic and security implications.

prone and crowded Malacca Strait, sandwiched between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. Obviously this carries economic and security implications.

Writing in the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in June, PoliTact’s strategist Claude Rakisits pointed out:

“However, in geostrategic terms the success of CPEC would not be good news for the US: it would displace the US as Pakistan’s major external patron in favor of China. Most importantly, it would provide China with a firm and reliable long-term beachhead in the Indian Ocean close to the Persian Gulf, effectively making China a two-ocean power. This would be a red rag to India.”

Thus if tensions between India and China, and matters related to the South China Sea, were to escalate, the BCIM strategic corridor is likely to become nonfunctional. In this case, CPEC would take on an added emphasis.

Then there are concerns regarding the stability of Middle East. The Middle East reigns as China’s largest supply of oil and energy: sixty percent of China’s oil comes from the Middle East, of which eighty percent originate in the Persian Gulf. These supplies travel from the Strait of Hormuz to Strait of Malacca, curling through the Indian Ocean and reaching China while passing through South China Sea, East China Sea and the Yellow Sea.

However, if the situation of Middle East continues to deteriorate due to extremism and continuing worries regarding Iran’s nuclear program, it is possible that the Strait of Hormuz itself becomes quite insecure. It is perhaps this assessment that led to the Russia-China $400 billion 30-year gas deal in May.

Where Does CPEC Fit In Pakistan’s Calculus?

While there is the tangent of how CPEC corresponds to the overall Chinese OBOR vision, the other angle has to do with the strategic importance of the economic corridor for Pakistan. Equally critical is how the Arab world and Central Asia would balance the various forces at play.

In a letter released at the opening ceremony of China-Arab expo 2015 on September 10, 2010, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated, “China and the Arab States are good friends with mutual trust, as well as good partners in seeking common prosperity,” adding that the Arab States have been reacting actively to his Belt and Road Initiative.

On the other hand, the potential mainstreaming of Iran as a result of the nuclear deal has created a new variable. Iran’s initial backing of Pakistan and Chinese supported peace talks in Afghanistan must be of concern to India.

These aspects, along with those described above, will be explored further in the upcoming articles.

About the Author

Kulsoom Belal is a South Asia and Asia Pacific (SAAP) Fellow at PoliTact.

Her research focus includes the impact of cruise missiles on South Asian ‘strategic stability’ and ‘stability-instability paradox’; military doctrines in South Asia, and is currently monitoring Iran for a think tank based in Islamabad. Her M Phil dissertation concentrated on US-China-India strategic triangle in the Asia Pacific and its implications for Pakistan’s Nuclear Deterrence.