Context

Context

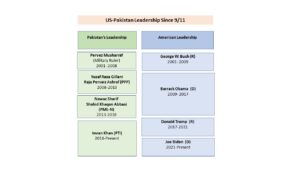

As Biden administration formulates its Pakistan policy, and reviews the Afghan peace deal reached in February last year – a debate is raging in both US and Pakistan based think tanks on the future of US-Pakistan relations. It is like a new season of an exciting Netflix drama serial, only that this one has been continuing for about two decades. For all intents and purposes Biden administration represents Season 4 of the US-Pakistan serial which has seen many twists and turns. During this period, several terms were used to represent the ties, such as ‘frenemies’ or a troubled marriage heading towards a divorce.

If we use this analogy, the serial started right after the 9/11 attack – represented by season 1 under Bush, followed by Obama’s season 2, and Trump’s season 3 just concluded on January 20th.

What may happen in season 4 requires an understanding of the plot. And the great debate ranging in the think tank world represent this assessment. One of the assertions is that although the nation has maintained an important position during the previous administrations, its likely to be low on Biden’s priority list. This emphasis is not much different than the approach adopted under Trump where military aid was cut to Pakistan. A greater emphasis was towards global adversaries than on countering extremism or promoting human rights. The analysts are thus suggesting areas around which convergences can be built.

Some have mentioned that Pakistan can help build bridges between US and China, just as it can between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Others have emphasized trade as the focus, and cooperation in dealing with the pandemic and climate change. As the balance of power in the Muslim world is shifting away from the Arab world and towards the peripheral nations of Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan, the country can play an active balancing role vis a vis the global powers.

On the other hand, Pakistan is stressing it has moved away from geopolitics to geoeconomics, as witnessed by CPEC like initiatives. This has been a consistent message from Pakistan’s National Security Advisor, Moeed Yusuf, who recently spoke at the Karachi council on Foreign Relations and Woodrow Wilson Center.

Under the Coronavirus induced circumstances, this could be interpreted to mean that the nations focus is on economics and less on engaging in another kinetic phase in Afghanistan – which has devastated Pakistan’s social fabric and economy. And this mantra goes along with the policy the present Prime Minister Imran Khan adopted when he came to power in 2018 – that it can help in making peace but not in the continuation of war. Just about the same time, US also shifted its position, which resulted in direct talks with the Afghan Taliban. Previously, Taliban had consistently refused to negotiate with the Afghan government, calling it a puppet.

In essence, as opposed to the thrust on military solutions that had remained the hallmark of Bush and Obama administrations, under Imran Khan, Pakistan’s assistance was focused on facilitating the peace talks with Afghan Taliban. The concentrated efforts, and cooperation from China, Russia, and Iran, resulted in an agreement between the US and Afghan Taliban in February 2020.

The peace deal was not arrived at easily and there were obstacles at each step of the way, consistently from the same sets of players. The very first challenge perhaps came from President Karzai when Taliban were allowed to open an office in Doha in 2013, carrying the sign and flag of Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. He argued that peace talks should be Afghan led.

In September 2019, the talks between the US and Taliban were abruptly broken off by President Trump – when peace deal was nearly at hand. Reportedly, he called-off talks due to an attack carried out by Afghan Taliban in Kabul that killed an American soldier. The confusion remained for some time if Trump had permanently abandoned the talks or if it was a temporary suspension. Moreover, he faced severe push back from Ashraf Ghani’s government. Senior former US officials with experience in Afghan affairs recommended US should not pullout before a real peace agreement, or in other words a responsible withdrawal.

Even when the deal was signed, everybody knew that the next step of intra-Afghan talks will be even more difficult, especially because of the role of spoilers, especially India. Heating global power tussles between US and China during the Trump administration added another dimension of worries. Up to now, global powers have cooperated when it comes to Afghanistan. Can it stay that way is not guaranteed.

As Biden administration evaluates its Afghan options, it is important to keep perspective of how we arrived at this juncture, what has already been tried. More importantly, to not get distracted under different pressures, especially when domestic challenges are mounting for the US. Keeping in view the historical context, about what can be achieved in Afghanistan at present – may not be possible six months from now.

How Did We Get Here?

Season 1 – 9/11 Attack (2001-2008)

Bush administration had been in power for about nine months when September 11 attacks struck the US. America launched Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) on October 7, 2001 with military strikes against Al Qaeda (AQ) and Afghan Taliban. The Taliban government crumbled quickly. While there were confrontations like the Battle of Tora Bora in December 2001, Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters mostly retreated to fight another day.

Bush administration had been in power for about nine months when September 11 attacks struck the US. America launched Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) on October 7, 2001 with military strikes against Al Qaeda (AQ) and Afghan Taliban. The Taliban government crumbled quickly. While there were confrontations like the Battle of Tora Bora in December 2001, Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters mostly retreated to fight another day.

Early on US pressured Pakistan to join what later became known as the Global War on Terrorism. The nation had been one of the few, including UAE and Saudi Arabia, that recognized the Taliban government. The military ruler General Pervez Musharraf decided to support the US and to go after former allies, the Afghan Taliban.

In the aftermath of the 1999 short and bloody Kargil conflict, then the army chief Pervez Musharraf had overthrown the civilian government in October 1999, removing Nawaz Sharif from power. For this US had slapped sanctions on his government, which were in addition to the ones imposed on Pakistan and India in the aftermath of the 1998 nuclear tests. For Musharraf’s support in Afghanistan, Bush lifted all sanctions on Pakistan in October 2001.

In the aftermath of the 1999 short and bloody Kargil conflict, then the army chief Pervez Musharraf had overthrown the civilian government in October 1999, removing Nawaz Sharif from power. For this US had slapped sanctions on his government, which were in addition to the ones imposed on Pakistan and India in the aftermath of the 1998 nuclear tests. For Musharraf’s support in Afghanistan, Bush lifted all sanctions on Pakistan in October 2001.

The 9/11 attacks presented an opportunity for Musharraf to gain international credibility. It was only later the realization dawned that AQ and Taliban had mostly slipped away from Afghanistan into the ungoverned Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA).

While US got distracted by going into Iraq in 2003, Bush administration increased pressure on Pakistan to launch military operations in FATA to eliminate what it termed as safe havens. Pakistan moved nearly hundred thousand troops from the Indian border towards Afghanistan to tackle the issue. US also conducted thousands of drone strikes in FATA between 2004 and 2018 to go after the extremist leaders hiding there. But Pakistan’s military operations in FATA, including the Lal Masjid operation in July 2007, accompanied by drone strikes, started to create an ominous backlash internally. It was unclear if the US drone strikes were occurring with Pakistan’s acquiescence – but it would publicly protest the strikes vehemently as violation of its sovereignty.

Many high value targets and facilities were hit in Pakistan as extremist reprisal spread, with thousands of civilian and soldiers killed and maimed. According to Dawn newspaper, Pakistan’s economic loss in the war against terror was a figure around $126.79 billion. The security and political turmoil, including the civil-military divide, was reflected by the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in December 2007.

By this time, the internal politics of Pakistan had gotten fully intertwined with the support it was providing US in the war against extremism and at what cost. While Musharraf had become increasingly unpopular, and US grievances with him grew, the death of Benazir Bhutto demonstrated that this was a battle for Pakistan’s survival too.

The Mumbai Attack in November 2008, just about a month and a half before Obama was inaugurated on Jan 2009, created fresh headaches for Pakistan on how it was dealing with good and bad extremists.

Season 2 – Obama’s AfPak

On assuming power, President Obama initiated an exhausting evaluation of the US Afghan policy, which later adopted the acronym of AfPak. The late Ambassador Richard Holbrooke was appointed to lead the office, whose mandate was to originally include India, but that part was dropped due to heavy lobbying from the country. This may have been a critical mistake, as India remains opposed to any negotiated settlement with Afghan Taliban .

.

At the time it was assumed that the new policy would break from the Bush era focus on kinetic approach, and tilt more towards a diplomatic surge and a search for political solutions based on a regional emphasis. Obama’s assessment went through a metamorphosis of sorts and ended up being an evaluation of the entire US foreign policy. Reappraisal of policy involved the critical questions of what is at stake for America in Afghanistan? Dealing satisfactorily with this inquiry required evaluating US interests globally, understanding how they are related and then prioritizing in terms of the prevailing economic recession at the time.

The strategy that finally emerged represented the competing institutional influences that shape American foreign policy. Obama had to balance domestic economic realities with the perception of appearing weak on national security threats, a leverage he did not want to offer to the Republican Party. Additionally, he also wanted to fulfill his campaign promises of pulling troops out of Iraq and focusing on Afghanistan. Specifically, the new strategy opted for sending 30,000 more troops while setting a timeline for an exit to begin by July 2011.

The new US policy was followed-up with a process of strategic dialogue with Afghanistan, India and Pakistan. What transpired from this dialogue with India was a civil nuclear deal, the groundwork for which was laid during the Clinton administration. On the other hand, Kerry-Lugar-Berman aid package ran into controversy because of provisions that many in Pakistan thought compromised its sovereignty. The Raymond Davis incident in January 2011 further validated Pakistan’s apprehensions. At the same time, Mumbai attacks and dealings associated with David Hadley, increased cooperation between US and India against groups such as LeT based in Pakistan.

Thus, the feeling of mistrust between US and Pakistan continued to increase, with both actors blaming each other for playing a double game. The Operation Geronimo gave further evidence of how deeply each party distrusts the other, while claiming to be strategic partners. The subsequent Memogate Affair, followed by the Salala Incident on November 26, 2011 further dented the relationship. A perception grew that the Civil-Military divide in Pakistan was being exploited.

During Obama’s tenure, war against extremism had expanded quite wide and included Yemen, Syria, and Libya. Moreover, by 2011 and onward the extremist threat had transformed as many new groups came in to being, such as Daesh (also known as ISIS and ISIL). Moreover, the Arab Spring related upheaval was further destabilizing many regimes in the MENA theater, to be exploited by extremists and other global adversaries.

had transformed as many new groups came in to being, such as Daesh (also known as ISIS and ISIL). Moreover, the Arab Spring related upheaval was further destabilizing many regimes in the MENA theater, to be exploited by extremists and other global adversaries.

As US was over-consumed by the war against extremism, China and Russia were resurging. China launched the Belt and Road global infrastructure initiative in 2013, with CPEC being one of its main arteries. At the cost $62 billion China plans to upgrade Pakistan’s infrastructure, build modern transportation networks, numerous energy projects and special economic zones.

While US remained busy with the war against extremism, the economy was impacted. The 2008 recession had a significant impact on the American middle class and a thought was taking shape that China, and even American allies, were exploiting Globalization – and US was paying. These sentiments were galvanized and channeled by Trumps ‘America First’ mantra.

Season 3 – Making American Great Again and ‘America First’

While July 15, 2015 Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA) was a significant step in the direction of negotiated settlement to conflicts, only a year and a half later President Trump reversed the deal. On the Middle East Peace Process, he went ahead to make the controversial decision of accepting Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

While July 15, 2015 Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA) was a significant step in the direction of negotiated settlement to conflicts, only a year and a half later President Trump reversed the deal. On the Middle East Peace Process, he went ahead to make the controversial decision of accepting Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Trump also stepped out of the Paris Agreement and annulled the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that Obama had pushed and was signed in 2016. In essence, Trump was against multilateralism and multilateral institutions and preferred bilateral approach to issues. Trump stated in his speech at the 74th UN session:

“Globalization exerted a religious pull over past leaders, causing them to ignore their own national interests. Those days are over.” He went on to add, “Around the world our message is clear, America’s goal is lasting, America’s goal is harmony, and America’s goal is not to go with these endless wars, wars that never end.”

While on the political and economic front he declared: “If you want freedom, hold on to your sovereignty, and if you want peace, love your nation. The future does not belong to Globalists. The future belongs to patriots. The future belongs to strong, independent nations.”

Following this principle, Trump supported direct talks with Afghan Taliban leading to the peace agreement. If it had not been for the Coronavirus, Trump would have likely won the election.

The storming of the Capitol Hill on January 6, and the events associated with the recent concluded US elections are reflective of the tremendous stress US is under to chart out its future direction; whether it be the globalized one or based on America First. The coronavirus has added to the woes – where many have lost jobs and the lifestyle of others acutely impacted – adding to the public anger and stress.

Irrespective of who is to blame for what transpired on January 6th, Biden administration would have to focus on how to bring the disillusioned, and the Trump supporters, back into the system. This is the best approach to prevent matters being further exploited. This implies Biden would have to address the concerns reflecting by the America First mantra – to provide jobs and to improve the economic well being of the Americans.

Season 4 – ‘America is Back’

Delivering a speech virtually at the Munich Security Conference on February 19, President Biden stated unequivocally that America is back. “I’m sending a clear message to the world,” Biden addressed the security conference. “America is back. The transatlantic alliance is back. And we are not looking backward.”

Delivering a speech virtually at the Munich Security Conference on February 19, President Biden stated unequivocally that America is back. “I’m sending a clear message to the world,” Biden addressed the security conference. “America is back. The transatlantic alliance is back. And we are not looking backward.”

On the other hand, soon after his acquittal from his impeachment trial in the Senate, Trump stated: “Our historic, patriotic and beautiful movement to Make America Great Again has only just begun”. His acquittal from Senate trial means Trump can run for office again in the election of 2024, which is likely to be the most consequential in American history.

The domestic politics is becoming increasingly polarized and that is directly linked to the state of the economy, which has been seriously dented by mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic. In such conditions, it would become increasingly challenging for the US to concentrate on foreign affairs, especially on the ‘unending wars’.

And it is in this domestic and global context the US-Pakistan relations, and the associated Afghan conflict, will unfold. There is no appetite left in Pakistan, and perhaps amongst European allies as well, for the continuation of the war other than supporting a reasonable exit. Whatever could be done, has been done, and now the responsibility lies squarely on Afghans. This message needs to be delivered – accompanied by reduction in violence on the Afghan Taliban side – associated by agreed withdrawal of troops on the part of the alliance.

The mantra of Trade not Aid is more prevalent as far as Pakistan is concerned. While China, Russia, Iran, and Turkey, have all supported the resolution of the Afghan conflict and have not linked it to their other frictions with the US, this cannot be assured in the future.

In other words, if US would make things difficult for China and Russia in other places and matters, they will now likely reciprocate in Afghanistan. While re-engaging with Iran on nuclear talks, and suspension of sanctions, may buy some favors with Iran – coming in and out international agreements have casted a long-term impact on US credibility. There was a time when American word was taken as ironclad, and leadership changes did not matter. Now US is telling the world to accommodate its dysfunction and confusion.

One of the fundamental question at this point is, to what extent will Afghanistan become a theater where global power tussles are going to play out. And thus – how critical is Afghanistan to undercut China and Pakistan’s influence in the region – and this is where the role of India, the Indo-Pacific, and the related Quad strategy fits in. The answer to this question makes the decision for US and NATO easier – if they should leave now and fight somewhere else – or stay. In other words, will Afghanistan remain an area of cooperation amongst global powers – or will competition ensue.