Context

Most conflicts arise from differences of perspectives as to how to view the world, which spring from historical contexts and interests, which in turn also frames threat perceptions. Power enables an international actor to impose its will and perspective on other actors, via coercion, the exercise of influence, diplomacy, or any combination of these. Power, of course, does not remain constant and most often it is assumed that there is a zero-sum dynamics involved. That is to say, one actor’s gain is another’s loss. Historically, during periods of shifts in power dynamics, tremendous upheavals have taken place; such areas are the settings of potential future threats. Such disruptions of the balance of power are usually settled decisively by wars. For example, the present system of governance came out of World War II: the United States became the preeminent world power, succeeding Great Britain and the victorious powers subsequently established the United Nations and the Security Council, with its five permanent veto-holding members.

Most conflicts arise from differences of perspectives as to how to view the world, which spring from historical contexts and interests, which in turn also frames threat perceptions. Power enables an international actor to impose its will and perspective on other actors, via coercion, the exercise of influence, diplomacy, or any combination of these. Power, of course, does not remain constant and most often it is assumed that there is a zero-sum dynamics involved. That is to say, one actor’s gain is another’s loss. Historically, during periods of shifts in power dynamics, tremendous upheavals have taken place; such areas are the settings of potential future threats. Such disruptions of the balance of power are usually settled decisively by wars. For example, the present system of governance came out of World War II: the United States became the preeminent world power, succeeding Great Britain and the victorious powers subsequently established the United Nations and the Security Council, with its five permanent veto-holding members.

At present, we are now witnessing the emergence of new centers of power, located in various spheres of influence: for example, the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China). This has led to disturbances to the existing balance of power, resulting in realignments to counter budding threats in today’s global and interconnected world.

Analysis

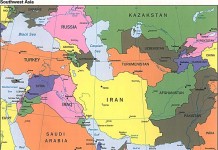

The Middle East is currently witnessing a rapid power shift. The creation of the state of Israel and the unresolved issues of Palestine and the status of Jerusalem dating to the post-World War II era have remained burning issues, with huge repercussions spanning the Muslim world. Numerous Islamic movements and revivalist groups were energized by the Palestinian hardships and loss of Al Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock, including the forefathers of AQ in Egypt.

The United States has long been the chief protector of the oil-rich sheikdoms of the Arab world, as well, of course, of the state of Israel. Saudi Arabia, on whose soil stands the holiest of holy places of Islam, is governed by a monarchy, which is not a system of government prescribed by Islam. The sheikdoms of the Middle East have been vehement on the Palestinian issue, which has given them substantial credibility in the Islamic world, but on a practical level, their dependence on the U.S. meant they could hardly do anything meaningful vis-a–is Israel’s policies regarding the Muslims of Palestine.

Historically, Saudi Arabia and even Saddam Hussein have provided substantial financial support to the Palestinian people’s jihad against Israel. After 911, Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Authority splintered, resulting in the emergence of the Fatah and Hamas groups. The pro-Western Arab countries reacted by supporting the moderate Fatah group, located on the West Bank, while Iran sponsored the Hamas, headquartered in Gaza, which favors military action. Egypt’s recent support has been critical to Israel’s attempts to block the border to Gaza and reduce support for Hamas. Furthermore, in 2006, Iran and Syria supported Hezbollah’s successful efforts to stand up to the might of Israel; many in the Muslim world applauded what they perceived as Hezbollah’s ability to humiliate Israel via small rocket showers.

Thus, the influence of Shiite Iran has increased incrementally at the expense of Sunni Saudi Arabia and its allies in the Middle East and South Asia. There has been a subtle shift in the Islamic public opinion regarding who genuinely stands up for its interests. Iran’s unwavering support of the militant Shiite Hezbollah and Sunni Hamas in the face of Israeli and American opposition has only increased the favorable images of Iran and the Shiite sect of Islam, while making pro-West Arab countries appear impotent. This was further illustrated in Iraq, where the United States had to rely on Iran to reduce tensions, at the cost of increasing Shiite influence in Iraq, which had been historically ruled by Sunnis, even though they are a minority. Another tension point is Lebanon, where Iran- and Syrian-supported Shiite groups (the Hezbollah) are far more influential then Saudi-sponsored Sunni groups.

Largely as a result of Israel’s harsh policies in Gaza and America’s Global War on Terror (GWOT), the military approach to the Palestinian issue gained ground and pro-Western Arab governments supporting negotiated settlement of the Palestinian conflict lost credibility among the Muslim public. Reacting to this situation, Prince Turki al-Faisal recently wrote in The Financial Times on January 22nd:

“So far, the Kingdom has resisted these calls, but every day this restraint becomes more difficult to maintain. When Israelis deliberately kill Palestinians, appropriate their lands, destroys their homes, uproot their farms and impose an inhumane blockade of them; and as the world laments once again the sufferings of the Palestinians, people of conscience from every corner of the world are clamoring for action. Eventually, the Kingdom will not be able to prevent its citizens from joining the worldwide revolt against Israel. Today, every Saudi is a Gazan, and we remember well the words of our late King Faisal:

“‘I hope you will forgive my outpouring of emotions, but when I think that our Holy Mosque in Jerusalem is being invaded and desecrated, I ask God that if I am unable to undertake the Holy Jihad, then I should not live a moment more.’ ”

These public pressures on – and historical rivalries between – Turks, Arabs and Persians have also exacerbated Turkey’s dilemma. Turkey’s Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, recently walked out of a panel discussion held in Davos, Switzerland. He also severely criticized Israeli President Shimon Peres for killing innocent people and children in Gaza. Turkey’s relationship is currently improving with Iran while deteriorating with Europe; some experts call this a symptom of Neo-Ottomanism.

With respect to Afghanistan, the U.S. need Iran’s help to pacify that country, just as in Iraq. In Afghanistan, the conflict is between the Sunni AQ, aided by the Taliban and the pro-Western Sunni Pakistani and Saudi governments allied to the U.S.

In Afghanistan, as in the Middle East, the Sunni Saudi government stands to lose if Iran’s sphere of influence grows. This prospect of the shift in the historic balance of power from Sunnis to Shiites is causing increasing concern to Sunni countries. This is part of the threat perception that is currently shaping the thinking of the establishment in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Pakistan has a double whammy to worry about: India, its traditional rival, is flirting with U.S., Pakistan’s ally. If U.S./Iran relations improve as a result of efforts to resolve the situation in Afghanistan, Sunni and Saudi influence may diminish even further.

This context explains why the Saudis have switched to fast mode in Afghanistan and Pakistan, using its influence with the Sunni groups and political parties who are open to negotiation. This is a challenge, for two reasons. The first is that these groups have long subscribed to the very different ideology propagated by the U.S., Pakistan and Saudi Arabia itself during the time of the Soviet Jihad. The second is that Iran is gaining new spheres of influence by adopting a militant policy and supporting clans hostile to the U.S., regardless of what Islamic sect they belong to. The latter factor explains why AQ and other affiliated Sunni groups, (for example, the Taliban), are gaining ground in Afghanistan and Pakistan, disseminating a militaristic approach against the West, the so-called pro-Western, puppet Muslim governments and the Shiites. These Sunni “terrorist” groups are filling the vacuum, increasingly viewed by the Sunni Muslim masses as their champions and enemies of Iran, to the great cost of pro-Western Sunni governments.