Context

By Dr Claude Rakisits

The royal rulers of Saudi Arabia must feel somewhat nervous of late. Seen from Riyadh, externally, the neighbourhood is not looking very hospitable and rather hostile towards the kingdom. And, internally, while matters appear to be under control under the newly-installed monarch, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, there must be a sense that domestically things could unravel if not handled properly in the future.

If matters worsen on either of these two fronts, the future of the country as we know it could look rather bleak. And any threat to the stability of Saudi Arabia is not only bad news for the future of the Saud dynasty but, given the pivotal geostrategic importance of the country, would be bad news for the region and the world. Accordingly, it is critical for all that Saudi Arabia navigate through these difficult and unchartered times as smoothly and successfully as possible.

Analysis

To The North

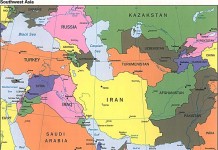

To the north, DAESH (Al Dawla al-Islamyia fil Iraq wa’al Sham) is lapping on the northern border of the kingdom. And even though the Saudis have built a high-tech barrier along the 1000 kilometres border which is made up of multi-layers of fencing, watchtowers and motion sensors and has deployed an additional 30,000 troops along the Iraqi border, DAESH fighters are successfully conducting raids against the Saudi security forces, killing soldiers and slipping into the kingdom. And while these armed engagements are limited today, the Saudi authorities’ bigger, long-term worry is the return to Saudi Arabia of some of the men who have joined DAESH in Syria and Iraq.

These battle-hardened and ideologically-driven fighters have already conducted terrorist attacks inside the kingdom. And while a number of plots have been thwarted before they were executed, we can expect more to follow and, inevitably, some will be successful. Worryingly, Saudi men represent one of the largest contingents of foreign fighters having joined the terrorist group. Reportedly, some 2500 Saudi men have already joined DAESH. And there is no indication that this recruitment pipeline is drying up.

To The South

To the south, Houthi fighters, who are drawn from a Shiite minority which used to rule a 1000-year old kingdom in Yemen’s highlands until 1962, have militarily defeated Yemen’s regular armed forces and now run the country. The former president, Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who was a close ally of the US in its fight against Al Qaeda forces in Yemen, has fled the country. Compounding an already bad situation, the Houthi guerrilla group is backed by Iran, Saudi Arabia’s arch competitor for regional dominance. Moreover, not only has the violent Houthi take-over not been welcomed by Yemeni society, but it has re-ignited the secessionist tendency in the south of the country. Although it is still too early to know how things will develop in Yemen, the odds are that Yemen will be a source of instability for the foreseeable future. This is bad news for Saudi Arabia.

To The East

To the east, Shiite Iran looms large on Saudi Arabia’s radar screen. Strategic competition between the two Gulf countries has been a permanent regional feature for several generations, but it has recently deepened with Tehran’s significant military engagement in Iraq to assist the government in Baghdad counter militarily the threat of DAESH. This latest development is in addition to Iran’s long-standing military assistance, advice and hardware to Shiite Hezbollah in Lebanon, its continued similar support to the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria who is allied with Hezbollah, and its supports for Hamas in Gaza. Compounding the discomfort such widespread Iranian involvement creates in Riyadh is Tehran’s not so covert nuclear arms program. And while the present negotiations between Tehran and the P5 + 1 dialogue partners may have slowed down Iran’s nuclear weapons program, Saudi Arabia remains unconvinced that the nuclear threat has diminished in the long-term. Finally, Iran’s ever-present influence and inspiration among the restive Shiite population in Bahrain and the eastern part of Saudi Arabia continues to worry the Saudi royal family.

The Blame Game

Seen from Riyadh, these external worries and problems could have been avoided had the Obama administration taken a different approach to the region. The late King Abdullah was not impressed with Washington’s eagerness to embrace the Arab ‘Spring’, particularly in the case of Egypt. Against the advice of the Saudis, President Obama decided not to support President Mubarak in his suppression of the Egyptian uprising. The Saudi monarchy took a very deep view of this position given that Mubarak had been a staunch supporter of the US in the Middle East for well over 30 years. Ironically, the US government ultimately acquiesced in General al-Sisi’s overthrow of the democratically-elected Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood president. Needless to say, the thought would have crossed the minds of the Saudi royals that the same lack of American support for a long-standing ally may well happen to them as well in the future.

The Obama administration’s approach towards Syria is another sore point in the bilateral relationship. Early on in the Syrian uprising the Saudis urged President Obama to support the moderate opposition but the US administration refused to get involved. And to make matters worse, when Syrian President al-Assad did cross the famous ‘red line’ with his use of chemical weapons against the civilian population, the Americans did not respond militarily as they said they would. By the time the US put together the multi-nation coalition to counter DAESH in autumn 2014, the Syrian opposition had been degraded and was no longer a credible military threat to the Syrian army.

Finally, the Obama Administration’s keenness to enter into never-ending negotiations with Iran over its covert nuclear weapons program did not please the Saudis either. From Riyadh’s point of view it looked as if Washington was more interested in accommodating Tehran’s concerns than looking after the interests of Saudi Arabia. Needless to say, President Obama’s approach to the region and overall handling of the Arab ‘Spring’ complicated an already inherently prickly bilateral relationship.

The Transition

Given this challenging external environment, it was essential that the transition to the new monarch following the recent – but not completely unexpected – death of King Abdullah be as smooth as possible. And seamless it was; transition plans were implemented to the letter and efficiently. This was vital to avoid any possibility by some restive sections of the Saudi population critical of the royal family to take advantage of this period. And although there does not appear to be any Arab ‘Spring’ in the making in Saudi Arabia, as with most Arab countries, Saudi Arabia has to cope with a large young population bulge, many of them unemployed. And with diminishing oil revenue, it is becoming increasingly more difficult to keep these young people satisfied. It is therefore not surprising that so many of these young people join DAESH in the misplaced hope that this will give meaning to their lives. The Saudi authorities will need to deal with this potentially explosive situation very adroitly.

In order to underline their understanding for Saudi Arabia’s challenging situation – externally and internally, and to underscore the critically important role Saudi Arabia plays in bringing stability to the region, many heads of state and government, including President Obama, President Hollande and Prime Minister Cameron, flew to Riyadh to show their support for the new king. It was also an opportunity for them to thank King Salman for his country’s participation in the coalition against DAESH. They did not need to remind King Salman of the importance of Saudi Arabia’s participation in this war against DAESH.

The Saudi royals would be the first to realise that an undefeated DAESH would pose an existentialist threat to the Saud dynasty. Given this potentially very toxic mix of a difficult neighbourhood and a delicate transition period domestically, this was not the appropriate time for the foreign dignitaries to bring up the subject of the desperate need to reform the Saudi political system, one that is utterly anachronistic in the 21st Century. However, in the not too distant future the Saudi monarchy will need to address honestly and fully the legitimate concerns raised by sections of its population and increasingly raised by its foreign friends and partners. Failure to do so may well bring about a greater existentialist threat to the monarchy than DAESH fighters knocking at the northern gates of the kingdom.

Saudi Arabia is a critically important player in one of the most important geostrategic regions of the world. It is in the interest of the region, in particular, and the international community, in general, that it deal successfully with the whole gamut of challenges it is now confronted with. Everyone would lose if it failed to do so.