Context

As the direct peace talks between the US and Afghan Taliban move along – the sixth round of talks started in Doha on May 1, while another session of talks were also facilitated by Russia from May 28-30. Meanwhile questions are being raised regarding the prospects of success.

To demonstrate the relevance of his government, and to counter the sentiment of being left out, President Ashraf Ghani convened the Loya Jirga in late April and also demanded a ceasefire. However, prominent leaders did not attend, which amongst others included CEO Abdullah Abdullah, Gulbadin Hekmatyar, and Hamid Karzai.

Any negotiations have to consider the positions of various stakeholders. More importantly, first the stakeholders have to agree to talk and then continue the process until a reasonable accommodation has been reached. Then there are spoilers. In this context, how can one evaluate the on-going talks keeping the perspectives of various parties in mind?

There are three main interlocutors to these talks: Afghan Taliban, the Afghan Government, and the US, which is also leading an alliance of foreign troops in Afghanistan. Meanwhile Pakistan is facilitating at this point and is not directly participating.

For US and Afghan Taliban to hold direct talks was a first step that indicated the willingness of the both interlocutors to engage. The US and Afghan Taliban have also held face to face discussions in the past, but they have been subject specific. For example, when both negotiated on the release of POWs – such as recently on the fate of US Army soldier Bowe Bergdhal.

The US has now decided to take a holistic approach to talks with the Taliban. According to Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad, there will be no agreement until everything is agreed upon. The primary focus areas include a complete ceasefire, foreign troops withdrawal, counter-terrorism assurances, and intra-Afghan dialogue. However, the sequencing of what comes first is proving to be challenging. What steps are taken first, gives an advantage to the other party, and means a loss of leverage for the other. Then there is the element of trust and how the agreed guarantees will be implemented.

On the other hand, the main demand of Afghan Taliban has been to hold direct talks with the US and complete withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan before moving on to other guarantees.

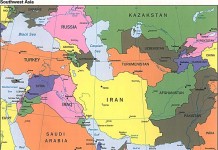

The achilles heel of the whole peace process is that other regional and global events are equally connect to what transpires in Afghanistan. The events include US-Iran tensions, US-China trade war, escalating Pakistan-India conflagration, and the introduction of ISIS in the Afghan non-state actor landscape. The longer it takes to develop a common ground over Afghanistan – the more complicated the talks become.

Analysis

US-Afghan Talks

According to media reports, the US wants an immediate and comprehensive ceasefire before it makes a decision on the shape of the withdrawal of forces. And Afghan Taliban would not offer a truce until it has a decision on the departure of foreign troops, and an agreement on the set up of future Afghan government. The intra-Afghan dialogue appears to be the last thing on the list. That does not mean contacts between the Taliban and other Afghan leaders and representatives are not taking place.

If US and Afghan Taliban talks were to succeed, Ashraf Ghani’s government, which is backed by India, a strategic US ally, has most to loose. Especially when the intra-Afghan dialogue has not fully taken off. From the Indian perspective, the success of Afghan peace process would mean Pakistan could fully focus towards it. Thus Pakistan-India détente is an essential prerequisite for peace in Afghanistan.

US-Iran Tensions

Then there are the secondary stakeholders of Afghan peace talks, which involve Iran, Russia, and China. In the face of unilateral US withdrawal from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA) last year and re-imposition of sanctions, on May 8 Iran decided to incrementally withdraw from the agreement too, unless the other signatories (UK, France, Germany, China and Russia) ease restrictions placed on its banking and oil sectors in sixty days.

These developments, including any military escalation, are bound to complicate the Afghan peace process. China and Russia are cooperating on the Afghan peace process, and a number of related meetings have taken place in Russia. However, China and Russia are also close to Iran, with China being the largest crude oil customer for Iran, and India the second. Iran is a vital pillar of Russian Middle East strategy, to include Syria.

Iran has also undergone a transformation of views regarding the Afghan Taliban. Because of its heavy involvement in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Lebanon, to Iran Afghanistan increasingly represents another flank – where it will likely confront similar dynamics as in the Middle East theater of operation. In this, the Afghan Taliban represent a saner local player for Iran to work with and to counter threats from ISIS and other Sunni extremists.

Thus Russia, China, and Iran can complicate the Afghan peace process if their tensions with US continue to increase, with US-China trade war also escalating. Although the cost of extended Afghan conflict are more for China, and its strategic ally Pakistan, than for the US. Nonetheless, engaging in talks with the Afghan Taliban helps to ascertain the positions of various stakeholders and then refine the strategy accordingly.

India-Pakistan Conflict

While the Pakistan-India tensions are known to flare up occasionally, the present one over the February 14 Pulwama incident has calmed down for the time being. However, in the absence of any political dialogue related to Kashmir, there is likely to be a next episode.

In the present circumstances,Afghan reconciliation would likely have a stabilizing impact on Pakistan and will reinforce its influence – possibly taking the region back to the pre 9/11 geopolitical environment. Using its strategic ties with the US, India has propagated the perspective that if the safe havens in FATA are eliminated, and with pressure on the Afghan Taliban, the present Afghan government has a better chance of succeeding.

India and Israel are the two states that have derived considerable political mileage since 9/11. They were able to label Palestine and Kashmir conflicts as being supported by extremists that are using violence to achieve political ends. The settlement of Afghan conflict will lend support to the argument that there is a difference between the terrorism unleashed by Al Qaeda andISIS- and what is talking place in Kashmir and Palestine.

In such circumstances, it is literally impossible to achieve Afghan reconciliation without getting India onboard and progress on India-Pakistan détente. In the post Pulwama environment, and with the reelection of Narendra Modi, the position of India is unlikely to change towards Pakistan.

ISIS Versus Afghan Taliban

The interjection of ISIS to the Afghan extremist landscape has added another hurdle to the Afghan peace process – that can possibly disrupt the traditional interlinkages of the extremist and proxy groups in the region, and potentially cause a conflict between India and Pakistan.

In 2014, PoliTact had noted:

“In the future, IS could become the centripetal force for disgruntled extremists of all sorts, leading to friction and infighting between various configurations of extremists, with the states caught in the middle, as is the case in the Middle East. This could further complicate Afghan reconciliation and normalization of Pakistan-India ties. On a more ominous note, ISIS could potentially compete against Pakistan’s alleged influence over some groups. While the consistent pressure on Core AQ may have indeed weakened it, the emergence of ISIS has created an opportunity and a focal point for the Associates of AQ to gravitate towards. This is a potent reason for Pakistan and India to resume results oriented dialog.”

This, however, should also be the reason and motivation factor for Afghan Taliban to hurry-up the reconciliation process, as ISIS will aspire to steal the platform. And while the grievances of Taliban are local, ISIS, like AQ, carries global agenda.

Conclusion

While in the past focus of the war against extremism has concentrated on state actions against non-state actors. The tussles of the global balance of power has transformed this campaign in to a full fledge proxy wars in many regions. Unless the basic framework that defined world politics in the aftermath of 9/11 is redesigned, the campaign is heading towards interstate conflicts.

Moreover, in the absence of any political resolution of the lingering Arab-Israeli conflict and Kashmir, the prospects for Afghan reconciliation are bleak. Meanwhile, new quagmires such as Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen, have been added to the sources of regional instability. Unless everything is settled, and the balance of power is once again restored, it would be naïve to think that a piece meal approach has a potential to succeed at this juncture. Will this balance amongst the global powers, and their regional allies, be restored militarily, or politically, remains to be seen – including how long it will take to achieve this.