How to Deal with Afghanistan’s Extremist Landscape?

How to Deal with Afghanistan’s Extremist Landscape?

Context

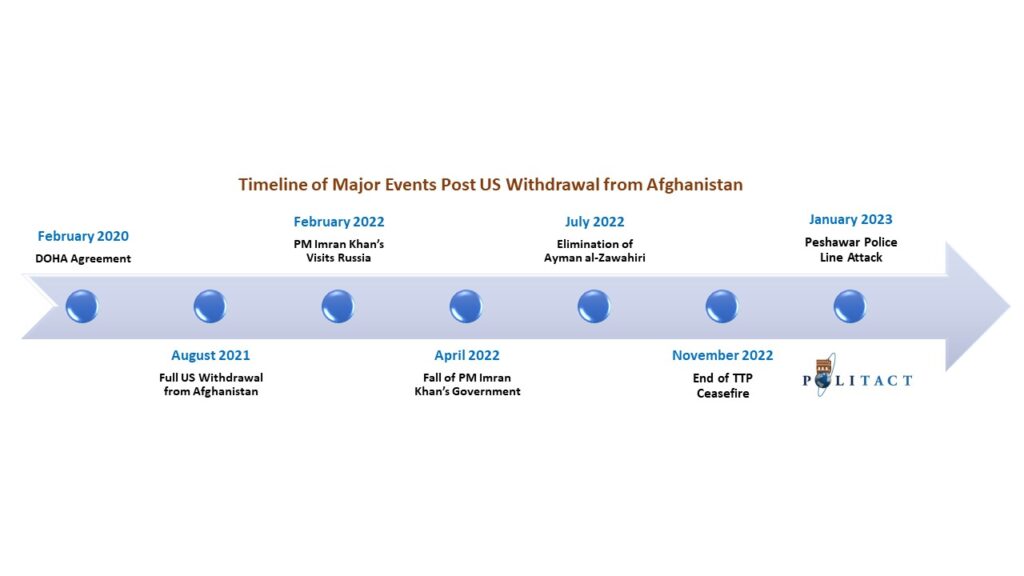

Since the full withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan in August 2021, it was assumed that Pakistan’s war against extremism had come to an end. There was a perception that the installation of Afghan Taliban in Kabul will make Pakistan’s regional influence grow. Besides, the nation was blamed for supporting the Taliban and providing them safe havens. Prior to 9/11 attacks, Taliban had extended its control to almost all of Afghanistan – and there were fears of its influence extending even further into Central Asia while threatening Iran. In 1998, 11 Iranian diplomats were killed in Mazar-e-Sharif in a battle between Iranian supported Northern Alliance and the Taliban forces – bringing the two close to a full blown conflict.

What transpired in the aftermath of 9/11 saw the reversal of the Taliban fortunes – and along with them with their supporters, particularly Pakistan. At the peak of the war against extremism, all major cities of the country were targeted by terrorists including its security forces. According to one estimate 83,000 lives were lost with an economic toll of about US$126 billion. The extremists accused Pakistan of supporting the infidels and providing bases and supply lines for NATO forces fighting Taliban.

However, since the US withdrawal, after a brief lull, the situation got progressively worse for Pakistan. Especially since the fall of Imran Khan’s government in April 2022. First came the elimination of Al Qaeda (AQ) mastermind Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul in July 2022, which demonstrated that Taliban were not holding up to their promise of breaking ties with AQ. Second, Pakistan was hoping that after US left Afghanistan, it could convince Taliban to act against Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). TTP had found refuge in Afghanistan since the operations carried out by Pakistan’s military in Swat and other Tribal Areas.

The horrific attack in Peshawar late January this year, which claimed the lives of more than 100 worshiping policemen, has reminded the country of the worse times of the war against extremism. This was followed by an attack on the police headquarters in Karachi on February 17. The country is once again grappling with the question of how to deal with Afghan Taliban and TTP.

Pakistan and TTP

Speaking at the Munich Security Conference on Feb 18, Pakistan’s foreign minister Bilawal Bhutto highlighted the risk:

“The concern is that if we and the interim (Afghan) government don’t take these groups seriously and they don’t demonstrate the will and the capacity to take on terrorist groups then they will conduct terrorist activities in the region first — we are already witnessing an uptick in terrorist activity in Pakistan since the fall of Kabul — but it won’t be long before it reaches somewhere else.”

He went on to add that Pakistan wants to work with Afghan Taliban to deal with TTP and to build its counter-terrorism capabilities, and is not looking to interfere in Afghanistan militarily. However, media reports indicate that Pakistan has targeted TTP linked leadership in Afghanistan several times since last April – and when Afghan Taliban are unwilling to assist. It reportedly carried out air strikes in April 2022 in Eastern Afghanistan. In August 2022, TTP commander Omar Khalid Khorassani was killed in a IED attack.

But it’s not clear if US desires to focus on the Afghanistan – as its attention is presently preoccupied with Ukraine, Russia, and China. Even Europe is in the process of decoupling from China. On the other hand, Pakistan claims China to be a strategic partner, and it was the former prime minister Imran Khan’s visit to Moscow in February 2022 that unnerved the US. Soon after, his government fell in April 2022.

Prior to his visit to Moscow and since the US Afghan withdrawal, a debate had been raging about how US would maintain pressure on the global jihadists present in Afghanistan from repeating a 9/11 type attack – or from pulling a serious attack on India. Reportedly, US had wanted bases in Pakistan from where to maintain kinetic pressure on global extremists in Afghanistan. Imran Khan’s government was vehemently against providing any such cooperation since his political mantra was based on a negotiated approach – at least as far as groups like TTP were concerned. Moreover, he had consistently questioned the wisdom of Pakistan’s previous involvement in the campaign against extremism in support of NATO at a tremendous cost of blood and treasure.

During his time in power, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) led government had sought Afghan Taliban assistance in pacifying TTP, resulting in a ceasefire that fell apart in November 2022 – and resumption of TTP attacks against Pakistan. The TTP demands related to release of prisoners were met to some extent. On the other hand, their requirements of decreasing the number of security forces in FATA – and rescinding of FATA merger are more complicated.

These conditions truly show that TTP aspires for a space from where AQ and Afghan Taliban can extend their reach. Moreover, how TTP wants to achieve these demands i.e., through terrorism – as compared to negotiations, needs to be transformed. To change the way TTP is going about its demands will require a change in Afghan Taliban thinking first. While Afghan Taliban were fighting foreign troops, there is no such validity in case of TTP – as it relates to Pakistan. TTP using the argument that it seeks to implement Sharia does not garner much merit.

To alleviate the source of TTP’s appeal requires integration of FATA into the mainstream while improving the infrastructure and economic wherewithal of the areas involved. Moreover, to empower groups like Pashtun Tahafaz Movement (PTM) in helping to bring the disgruntled towards political inclusion and addressing grievances.

US and TTP

The presence and elimination of AQ mastermind Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul was a clear violation of Doha Agreement reached in February 2020. One of the key terms of the treaty stipulated Taliban will not allow Al Qaeda, ISIS-K and other International terrorist groups and individuals to use Afghan territory to launch attacks against US and its allies.

These allies could be interpreted to mean India and Pakistan. Over the years Afghanistan has become a hotbed for extremists from all brands. For example, AQ and Daesh (ISIS-K) targeting the US prior to withdrawal, TTP carrying out attacks against Pakistan, Lashker-e-Taiba (LeT) and related groups striking India, while East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) was linked to terrorist activities in China. What Bilawal’s comments quoted above may be referring to is the nightmare scenario of a terrorist attack occurring in India which can trigger a wider regional war.

A report published by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) recently indicates that on one hand US does not consider TTP to be a direct threat to US – but at the same time worsening security situation of nuclear Pakistan is deemed a security concern for the US.

The reality is there is an ominous lack of public support and political consensus in Pakistan on how to deal with extremists, especially with the likes of TTP. Additionally, the economic woes of the country prevents it from dealing aggressively with extremism. This could change if TTP were to launch and claim more deadly attacks within Pakistan. On the other hand, if the threat perception from TTP were to change towards being perceived as a direct threat to the US – the calculus could alter. Moreover, if fresh elections are held in Pakistan, and Imran Khan governments returns to the helm, he may take a different approach to dealing with TTP and galvanize public support.

While it remains unclear where the assets used for eliminating Ayman al-Zawahiri were based, it’s clear that US retains the capability to deal with risks from global extremists that directly threaten it. Will US allow these assets to be used against TTP, like in the past, remains ambiguous. Pakistan needs to develop a wider political consensus on how it wants to deal with extremism and reevaluate its ties with Afghan Taliban. This is very difficult to do for a nation amidst political and economic meltdown.

Understanding Afghan Taliban

The evolving extremism landscape in Afghanistan provide hints towards the future of the campaign against extremism. As Afghan Taliban have settled in – it’s not clear if they are willing to break ties with global extremists such as AQ, or act against local affiliates like TTP. On the other hand, its ability to counter ISIS-K is also questionable. So far, it’s not accepted any assistance in this regard fearing being labelled as a Western collaborator. Attacks from Baloch Liberation Front (BLF) in Pakistan are also on the rise, especially related to CPEC.

The opportunistic postures of Afghan Taliban are meant to exploit the fears of stakeholders like US, China, Russia, Pakistan, India, and Iran – and by maintaining a leverage of extremism over all of them. For example, it has kept the TTP gambit over Pakistan, while at the same time offering India to keep a check on LeT and Al Qaeda in the Indian Sub Continent (AQIS), and then delicately adjusting its policy towards global extremists (AQ and ISIS-K) and other Western concerns – including women rights and inclusion of minorities in governance.

Writing in the National Interest after his recent visit to Afghanistan, former senior policy advisor to the US State Department Secretary’s Office of Religion and Global Affairs, Qamar-ul Huda commented: “Washington must realize that religious-political actors like the Taliban are acutely aware of their value in regional politics; they understand that local governments and global coalitions are seeking them out to counterbalance the weight of violent extremism and build multilateral ties for stability and economic benefits. The key question is whether the Taliban can transform from militia-minded fighters to nation-building technocrats and deliver for Afghanistan.”

Speaking at a webinar organized by Karachi Council on Foreign Relations on January 11, 2022 Taliban’s Representative in Pakistan Sardar Ahmed Khan Sakeeb took a stance on Durand Line that is not much different from the Ashraf Ghani and Karzai governments. He stated that his administration wants to take the matter to the Afghan people and then discuss the matter further.

On relations with India and Pakistan’s apprehensions, the Taliban representative explained that they wanted to pursue economic and political relations with India, and will not make it an enemy because of Pakistan, or make anyone else an adversary because of India – and this is beneficial for all. Replying to criticism for not speaking up for Indian atrocities in Kashmir, he added that they will speak out whether the atrocities are being committed by India or anyone else. He advised on solving all matters though negotiations.

Conclusion

The unfolding scenario of Afghanistan is directly impacting the political and security situation of Pakistan. Its ability to convince Afghan Taliban to act against TTP has only produced facilitation of negotiations. This has greatly frustrated the new Pakistan government and perhaps has pressured it towards more counter-terrorism cooperation with the US – for which there is little public buy-in in Pakistan. And this puts the economically fragile nation in a quandary.

Faced with growing US-India strategic partnership, counter-terrorism cooperation with the US could provide the security and economic lifeline Pakistan desperately needs. However, US has shifted away from counter-terrorism to strategic competition with China and Russia. And thus, the question becomes where do Afghan Taliban, including regional and global extremists, and for that matter Pakistan, fit in the great power rivalry equation. On the other hand, it’s likely the joint pressure of China and Pakistan, to protect their common interests, could nudge the Afghan Taliban in the direction of more serious action and curtailing the activities of TTP, ETIM, and BLF.

Correction: A previous version had stated Omar Khalid Khorassani was killed in a drone strike – he died in an IED attack.