Context

By: Farooq Yousaf

By: Farooq Yousaf

Since its inception, the state of education in Pakistan has presented a grim picture. With the onset of militancy and extremist narrative, the situation has become worse. With FATA in the firm grip of militants, the literacy has further dropped from 29% to just 17%.

Pakistan has, time and again, been included in the list of developing countries, but unlike its competitors, it has a drastically low literacy rate. Only one fourth of adults in the country are literate, and just 2% of the GDP is spent on education. This reflects the seriousness policy makers have shown to improve education levels. Although Pakistan has faced various crises over the past decade, education was never given due attention. This lack of focus could also be one of the causes for the escalating of militancy in Pakistan.

Opinion

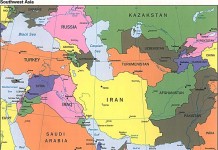

The militancy and violence in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan has consistently drawn world attention. After 9/11, the wave of terror which hit Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and FATA, and then other parts of Pakistan, has not only impacted the economy but also the education system of the country and KP.

The province, which traditionally was known by its hospitality, now provided sanctuaries and breeding ground for the militants. Schools were blown up, and students were threatened not to pursue the worldly education. This was based on Taliban’s version of Islam that discouraged worldly orientation, particularly for females, confining women to home with no right to education or recreation. These practices were enforced in the name of Islam.

The roots of the deteriorating state of education in the region can be traced back to the 80’s when President Zia’s regime supported the US war against Soviet expansion in the region. Religious schools, commonly known as Madrassa (or plural- Madaris) were transformed into Jihadi training institutes. Rural students seeking education in madaris were indoctrinated to become guerilla fighters in the name of religion and war against the infidels (communists).

Curriculum developed for these madaris propagated militant Islamic Jihad, contributing to the evolution of extremism in Pakistan. Even today, the madaris are perceived as a source of affordable education in the rural areas of KP. However, for the world outside, these madaris are breeding grounds for militancy. And, as most of these remained unregistered, they stayed outside the state regulation that helps keep a check on their activities.

As terrorism and Taliban indoctrination spread, there were other social impacts. Recreational and extracurricular actives were halted in schools, and female students were pressurized and threatened to use veils. Learning institutes in which boys and girls studied together constantly received warnings of suicide attacks, producing a permanent sense of fear and panic among the students.

Faizan Azeem Khan, a student for a bachelor’s degree from South Waziristan (FATA) commented:

“We used to visit our village regularly before the onset of militancy in our region. Militancy has set us apart from our relatives, and in current scenario I don’t think I’ll ever get a chance to have a reunion with them in Waziristan. This situation has put a drastic effect on my education due to stress and anxiety. The militants only seem to have one agenda mind, that is, stop the youth from attaining Worldly Education.”

The current government, to a large extent, shares the responsibility for not taking solid measures to curb militancy through education. As a result of militant attacks in KP, more than 700 schools have been destroyed, causing a loss to infrastructure worth millions of dollars.

The already low spending on education, 2.5% of GDP in 2006, was further cut down to 2% by 2012. Militancy, coupled with substantial cuts in spending on higher education, has led to suspension of various key projects in KP.

Higher education projects planned for Hangu, North Waziristan and Bajaur had to be shelved due to fear of reaction from militant organizations. As a result, hundreds of scholarships offered for FATA students were wasted. This was heartbreaking for thousands of students for whom the universities of Peshawar were inaccessible. The staggering difference between the education standards of public and private sector, leads to decreasing employment opportunities for the underprivileged class, generating a sense of frustration. This disappointment is also cashed in by the militant organizations.

The recent decision of the Federal government to transfer Higher Education Commission under the purview of the provincial government also hurts the future of education in Pakistan. The financially weak provinces cannot provide for this function.

The government needs to realize that maintaining an ambiguous policy on militancy and keeping a minimal level of spending on education and development would not help in nurturing moderate leaders for the country. Calls for total eradication of religious seminaries (or the madaris) also makes little sense as most of Pakistan’s population, which is already living below the poverty line, depends on this free source of education.

Grass route reforms, such as those introduced by the nonprofit sector, need to be incorporated in these seminaries. Such as, imparting vocational and computer skills for students seeking religious education. In coming years, bringing reforms to the structure and curriculum for madaris would be of utmost importance. This is essential in order to nurture a generation that is equipped to face the challenges of the future.

The writer is a Research Analyst, Programme Consultant and Content Editor at the Centre for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) in Islamabad, Pakistan. He is also pursuing research studies in Public Policy from Germany. His major areas of interest are War on Terror, Militancy in FATA, Central Asia and Middle East. He writes for major Pakistani and International news sources and can be reached at farooq@crss.pk