By Arif Ansar and Dr Claude Rakisits

By Arif Ansar and Dr Claude Rakisits

Context

For all intents and purposes US is entering the third stage of its military engagement in Afghanistan. The first one was right after 9/11 when George W. Bush launched an attack against the perpetrators and their supporters, Al Qaeda and Afghan Taliban respectively. The second phase was represented by the tenure of Barrack Obama, while the third stage is reflected by the arrival of Donald Trump to the helm.

As President Trump’s review of the Afghan strategy nears completion, the suspense continues on what may be the way forward. As has happened in the past in regards to many other recent deliberations, including related to Iraq, the political pundits are narrowing the debate to a few simple options. And because of this, the alternatives appear to be limited. It is very similar to when President Obama ordered his review of the Afghan strategy – and the generals presented him with few options. He had to go around, to diversify the choices on the table.

Leaders often have to be creative to broaden the alternatives available, to not get boxed in, and to augment sophistication and flexibility in their decision-making. Moreover, policy has to stay attuned to the changing circumstances otherwise it risks becoming irrelevant, this is especially true if the conflict is spread over a protracted period of time

Options

The present options seem to include:

- The troop levels in Afghanistan, and more importantly, their mission. Linked with this question is preparedness of Afghan Security Forces (ASF), and the weapons they need to take on the challenge head on. For example, the lack of air support has emerged as one of the key limitation for ASF.

- The role of Pakistan to bring about reconciliation in Afghanistan, and at the same time exerting military pressure against Afghan Taliban. Associated with this challenge is whether to utilize carrot or sticks towards the country – where allegedly the safe havens for the dreaded Haqqani Network still persist.

- Should Afghan policy be linked to Pakistan and India dynamics? As happened early on during the Obama presidency, there was an attempt to make this association, but under pressure from the Indian lobby the strategy was left with the acronym of Af-Pak. This does not imply that that the policy was oblivious to this dynamics, especially in the aftermath of 2008 Mumbai Attack, but it was relegated to behind the scenes dealing.

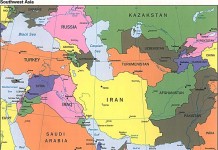

Absent from public debate is the realization of how complex the geopolitical and geo-economic reality has become. The global campaign against extremism and the transition in the global balance of power have become fully intertwined. As PoliTact had forecasted, the dynamics of the Middle East has now caught up with that of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Moreover, China and Russia are both involved in the Afghan Great Game – and it is critical to look at Afghanistan from the eyes of China, Russia, and Iran too. In other words, the American South Asia policy will have to be understood in relation to how these powers view the region and the role of the Afghan Taliban.

Understanding What Afghanistan Means for China, Russia, and Iran

Russia

The significance of Afghanistan for Russia has increased gradually, especially after the West imposed sanctions on Russia due to its actions in Crimea and Ukraine. Russians have felt that while it was cooperating with the West on a number of global concerns, and in relations to extremism, NATO was not reciprocating. Additionally, NATO did not desist from its expansion activities in the Russian Near Abroad.

In the Middle East too, Russians had been slowly loosing ground and it no longer enjoyed the kind of influence it once had under the Soviet Union. The removal of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi further reinforced Russian sensitivities. In case of Libya, China and Russia shared the position that NATO went beyond its stated objective, and that foreign powers should not interfere in the affairs of sovereign states. This was one reason that Syria became such a test case for Russia, forcing it to intervene military and come to the defense of its ally.

Russian involvement in Syria is not just to fight extremists, but more importantly to protect an Arab Spring-inflicted ally, whose government provides military facilities for the Russians. In essence, Syria occupies a key position for Russian power projection in the region and beyond.

Timing was another factor. As EU went through an economic recession, Putin watched keenly and exploited the vulnerabilities – especially in the energy sector. Russia has also been working on building closer ties with France and Germany. Moreover, Putin saw that after heavy military involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq, the US was over-stretched. However, when NATO started to re-exert itself in Syria and Europe under Obama, Russians slowly started to get more involved in Afghanistan and to nurture this leverage as part of a grand plan. This was occurring when Russia and China were also working with the US on the Iran nuclear deal.

Nonetheless, Russians initially established contacts with the Afghan Taliban. Moreover, they started to develop better economic and defense ties with Pakistan, despite opposition from its staunch Cold War ally, India. More recently, reports have emerged that Russia has also started to arm the Afghan Taliban and launched its own peace initiative for Afghanistan, which has had several meetings. The Russian’s consider Afghan Taliban to be the bulwark against the spreading influence of Daesh in the region.

Iran

Another Russian ally in the Middle East, Iran, has also undergone a transformation of views regarding the Afghan Taliban. Because of its heavy involvement in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Lebanon, to Iran Afghanistan increasingly represents another flank where it will likely confront similar dynamics as in the Middle East Theater of Operation. In this, the Afghan Taliban represent a saner local player for Iran to work with and to counter threats from Deash and other Sunni extremists.

China

Meanwhile, China has launched its “One Belt One Road” economic initiative, and one of its tributaries is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. The success of the economic corridor is heavily dependent on the security situation of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Moreover, China has its own concerns regarding extremism sprouting from the region and impacting its Muslim population. Gwadar Port provides China an alternative sea access in case the Strait of Malacca was blocked, and there are rumors regarding militarization of this port at some point in the future.

China’s concerns on US and NATO policies are not significantly different from the Russians’. After all, this conformity of views is what led to the successful creation of organizations such as Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which recently included both India and Pakistan into its fold.

As is the case for Iran and Russia, Afghanistan represents another flank for the Chinese. As for the other flank, at its core, China is anxious regarding the emerging US policies in the Pacific region, which includes Taiwan and the “One China” Principle. Additionally, China’s draws a parallel to the situation in the Middle East – and whether a regime changes-type formula might be applied to the rash regime of North Korea. Not surprisingly, China and Russia have both protested the deployment of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) ballistic missile defense system in South Korea. Russia has similar apprehensions for the American Missile Defense Shield in Europe, which apparently is meant to counter missile threats from Iran – but Russia thinks the system is directed towards its capabilities.

Domestic Politics of Pakistan, Afghan Policy Review and India Ties

As this global context evolves and the American review of Afghan policy continues, the domestic politics of Pakistan is becoming unstable, seemingly oblivious to the regional and global situation.

Last week the Supreme Court of Pakistan unanimously declared that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was not “honest” and that therefore he was “disqualified to be a member of Parliament”. Mr Sharif subsequently resigned, promising to use all available legal and constitutional means to challenge the verdict.

This long-awaited decision was the culmination of over a year of investigation into the business affairs of the prime minister and three of his children following disclosures in the Panama Papers. The Sharif family members were unable to provide valid documentation to prove how they had accumulated such vast wealth, including very expensive London apartments, in a legitimate fashion.

Sharif’s departure is unlikely to change much domestically and externally, especially given that he will retain the leadership of his party, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N). It’s ironic that Sharif’s disqualification was based on constitutional amendments put in place during President Gen Zia-ul-Haq’s rule (1977-1988) given that Gen Zia was effectively Sharif’s mentor who helped him establish his political credentials in Punjab.

Needless to say, Sharif’s supporters believe all this to be a conspiracy by the military which was determined to get rid of him once and for all. It’s important to remember that Sharif hasn’t always had a good relationship with the country’s all-powerful army. His first stint as prime minister ended when the Chief of the Army Staff forced him to resign in 1993 following corruption charges. His second premiership was cut short in 1999 when Gen Musharraf toppled him and sent him into exile in Saudi Arabia for the better part of a decade.

During this third term, which started in 2013, Sharif’s relationship with the military was also strained. Soon after taking office Sharif was determined to negotiate with the Pakistan Taliban (the TTP as it is known here) as he had promised during the election campaign. The army was dead set against these talks, having lost 5000 men fighting the terrorists in the tribal areas along the border with Afghanistan. These talks, which were going nowhere, ended following an attack on Karachi airport in June 2014. Following the horrendous TTP attack on a school in December 2014, the military was determined that its wide-scale operation in the tribal areas would hunt down all militants, Pakistani and Afghan. On the whole, this military operation has been effective in eliminating, degrading and disrupting the various terrorist groups.

However, there is still lingering suspicion in the higher echelons of the military and the bureaucracy in Washington that the Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani Network are still getting assistance from elements of the Pakistan military for their attacks against civilian and military targets in Afghanistan. These doubts as to whether Pakistan is running with the hare and hunting with the hounds is nagging American policy-makers. So increasingly officials are wondering what sort of pressure can be put on Pakistan to change its ways.

The chairman of Pakistan’s Senate Defense Committee, Senator Mushahid Hussain, recently said at a meeting here in Washington that he was hoping that there would be clarity from the Trump administration on its approach to South Asia. Unfortunately, given the internal infighting in the White House on this issue (and many others), it’s unlikely that we will be getting clear guidance on this matter in the near future.

When it comes to Pakistan’s relationship with its two large neighbors, China and India, no one expects any changes. Chinese officials were quick to reassure everyone that CPEC wouldn’t be affected by Sharif’s downfall. As for India, no one is expecting changes either in the bilateral relationship, if anything, it will probably get worse before it gets better. There had been much hope that PM Modi and PM Sharif—two business-friendly leaders—would move the relationship forward. However, nothing came of that, instead relations deteriorated in the wake of terrorist attacks in India by Pakistan-based jihadists.

So while on the whole the ousting of Nawaz Sharif is good news for trying to improve the poor state of governance in Pakistan. It’s unlikely to make too much of a difference in the long-term. Many more corrupt politicians would need to be disqualified to run for office before the people of Pakistan would be convinced that there is a genuine change in the air.

Proof, if proof is necessary, that little will change is the fact that Nawaz Sharif had chosen his brother, Shahbaz Sharif, who is the Chief Minister of Punjab, to eventually replace him as prime minister of Pakistan. However, there’s a feeling in the party that it might be best not to replace Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, the newly-installed temporary prime minister, and instead let him contest the federal election due to be held around June 2018. Regardless as to who is eventually chosen as prime minister, as leader of the party, Nawaz Sharif will make sure that his successor makes no changes without his approval.

The question becomes, under this political instability will Pakistan be able to meet the demands that may result of the American Afghan policy review. Pakistan’s political setup is increasingly busy with infighting and is unlikely to be able to focus and deliver when it comes to Afghanistan. Moreover, tensions in the civil-military relations will further complicate implementation when it comes to matters of Afghanistan and India. The risk being that similar to the recent events of Turkey and Saudi Arabia, a hardliner could emerge.

American South Asia Policy

On Pakistan’s security concerns vis-à-vis India, US has traditionally taken a balanced approach. However, this began to change during the era of Bill Clinton, when foundational steps for building strategic ties with India were laid. This policy has continued over Democratic and Republican administrations and now is reaching maturity. Under President Trump, the trajectory is likely to continue.

The dilemma for US policy has continued. Pakistan has and offers to cooperate in the campaign against extremism when it comes to those groups that carry global ambitions – but it is quite sensitive to protecting its interests when it comes to India. US has used the political, economic, and military leverages at its disposal to try to change Pakistan’s behavior in this regard, but those have had limited efficacy.

In the evolving balance of power of the region, China and Russia have moved closer to Pakistan, which otherwise was a customary US partner. On the other hand, Russia’s Cold War ally, India, has moved heavily towards the US. Afghanistan itself is building its ties with both China and Russia but the regime’s heavy dependence on Western support for survival would only allow it to go so far in that direction.

In this context, American détente with Russia has become a necessity not a desire. US appears willing to show flexibility over Syria and to entertain Russia. However, Trumps romance with Putin has deeply worried the European powers and the domestic opposition has also continued. With American flexibility over Syria, Russia would have likely reciprocated in the South Asian theater. Moreover, the détente with Russia would have been a bad omen for Russian and China bonhomie, BRICS and SCO, including Iran.

In the prevailing political atmosphere of the US, the detente with Russia looks unlikely. This will only increase the utility of Pakistan over time, like Saudi Arabia in the Middle East, to counter Iran and Russia.