Context

By Chris Zambelis

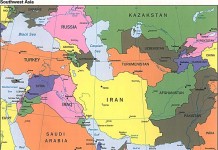

The full repercussions of Russia’s growing involvement in the Syria conflict in the form of overt military action have yet to be realized. Until now, Moscow’s support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s Ba’athist regime, in concert with ongoing support furnished by Iran, Lebanese Hezbollah, and Iraq, has proved critical to its survival in the face of an ever expansive insurgency.

Despite its embattled disposition, the Ba’athist regime remains without question the most powerful actor in Syria’s civil war. The conflict has come to be typified by a muddle of armed opposition factions represented by competing radical Islamist currents led by Daesh (“Islamic State”) and al-Qaeda’s Syrian-based franchise Jabhat al-Nusra and a host of other hardline Islamist militants that straddle the ideological divide between both camps. The far less impactful yet nevertheless notable cohort of insurgents associated with the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and its multiple iterations continue to solicit and receive moral and military support from the U.S. and other Western nations and their allies in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

The impact of Russia’s direct intervention in the form of air strikes and other kinetic military operations in support of the Ba’athist regime is profound. While the debate surrounding Moscow’s strategic objectives in Syria remains subject to conjecture, there is little dispute over Russia’s potential to affect the conflict’s trajectory. At the same time, Russia’s elevated profile in Syria cannot be considered in a vacuum absent of the activities and pursuits of other foreign actors, including Saudi Arabia.

The intersecting conflicts of communities, ideologies, and interests that underlie Syria’s civil war have become party to an equally convoluted, multilayered proxy struggle that transcends the Middle East. In this regard, charting Russia’s interface with Saudi Arabia, a driving force behind the armed opposition to the Ba’athist regime, is critical to unpacking at least one facet of the Syrian imbroglio. With the October meeting between Saudi Arabia’s Deputy Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman al-Saud and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin in Sochi, Russia and a public declaration by Saudi clergy affiliated with the political opposition in the kingdom calling on Muslims to wage violent jihad against Russia as the backdrop, the Russo-Saudi clash over Syria merits further examination.

Analysis

Fleeting Rapprochement

In light of the widely acknowledged deterioration in Saudi-Russo relations over Syria, many observers assessed a positive shift in bilateral relations between the longtime rivals only a few months prior to Moscow’s bombing of armed opposition groups in Syria. The circumstances surrounding the June 2015 meeting between Muhammed bin Salman and Putin are a case in point. Having occurred on the sidelines of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, the meeting between the historic adversaries produced six agreements governing the spheres of oil and natural gas, space research, the peaceful use of nuclear energy and the sharing of nuclear technology, and military-technical cooperation. Muhammed (who at thirty years old also holds the portfolios of second deputy prime minister and minister of defense) and Putin also discussed a range of other issues in what both sides hailed as a friendly and overall positive climate. In a sign that both sides were committed to build upon the momentum from the June talks, Muhammed extended an invitation to Putin to visit the kingdom while Putin reciprocated with an invitation to King Salman bin Abdelaziz Al Saud to visit Russia.

The seemingly positive shift in relations between Saudi Arabia and Russia was explained by numerous factors. Among these included the diplomatic breakthrough surrounding Iran’s nuclear program. The impact of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) signed between Iran and the so-called P5+1 (the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany) continues to reverberate strongly in Saudi Arabia. In exchange for its agreement to not pursue a nuclear weapons program and to agree to other restrictions on its nuclear activities, Iran will see most of the international economic sanctions levied against it lifted.

The landmark agreement lays the groundwork for the steady rehabilitation of Iran’s position in the international community. Iran’s return to the world stage will have far reaching strategic implications for Saudi Arabia and the wider Middle East and international energy markets. Despite its strategic alliance with the U.S. and assurances from Washington over its commitment to the preservation of close relations with Riyadh, Saudi Arabia worries that the emerging détente between Washington and Tehran portends an eventual rapprochement that will reshape the regional and international landscape at the kingdom’s expense. Even as it continues to tout its longtime position as a major swing producer and exporter of crude oil, the prospect that Iran, an energy powerhouse in its own right, will realize its full potential as a producer and exporter of both crude oil and natural gas represents another cause of deep concern in Riyadh, which fears having to contend with greater Iranian supply and the residual negative impacts on energy prices that would result. Iran has already elicited strong interest from major international energy companies eager to reap the rewards of Iran’s vast wealth of untapped potential in the oil and natural gas sectors.

Consequently, the logic that underlined Saudi Arabia’s apparent openness toward Russia was couched as an attempt on the part of the Riyadh to diversify its portfolio of diplomatic relations to lessen its dependence on Washington. Likewise, Russia’s apparent willingness to more closely engage with Saudi Arabia is also worth viewing through the prism of the Iran nuclear agreement. Moscow’s reaction to the JCPOA has largely been overlooked.

On the surface, Russia has welcomed the agreement. Yet the prospect of Iran’s reintegration into the international community presents Russia with numerous challenges. Russia has successfully leveraged Iran’s diplomatic and economic isolation to great effect over the years. From the Kremlin’s vantage point, hostilities between the U.S. and Iran, for the most part, have served a useful purpose in the form of distracting and otherwise preoccupying Washington, forcing it to devote significant attention and resources that could have otherwise been concentrated toward Moscow. Russia has leveraged its diplomatic and economic influence over Iran as both a lever of influence over Washington and the international community. As a major producer of oil and natural gas, the economic sanctions levied against Iran have helped to protect Russia’s market share and favorable energy pricing schemes even given the prospects for Russian investment in the Iranian energy sector. The Iranian energy sector is poised to compete with Russian exporters in the vital European market.

Iran’s isolation had also helped foster close diplomatic and economic ties between Moscow and Tehran that had come to resemble a special relationship. Russia found common cause with Iran in their shared opposition to the U.S. and numerous other Western-led institutions and policies and mutual advocacy for the creation of alternative structures and approaches. Indeed, with few alternatives, Iran had come to depend greatly on Russia as both a vital economic outlet that helped it circumvent economic sanctions, as well as a diplomatic interlocutor that was often advocating on its behalf in the international community. The extent of Russia’s support for Iran’s defense and nuclear sector is also well known. Russia and Iran have also expanded their cooperation into the military and intelligence spheres in Syria and Iraq.

Despite a genuine sense of shared concern over the circumstances surrounding the Iranian nuclear agreement, the gravity of the developments in Syria would outweigh any possibility of a transformational shift toward the positive in Saudi-Russo relations. The degree of mutual enmity shared between Saudi Arabia and Russia regarding the conflict in Syria and a host other matters would suggest that any potential breakthrough in relations would be illusory or, at best, fleeting.

Standoff in Syria

The conflagration in Syria has quickly escalated into a staging ground for a host of proxy conflicts with ramifications that transcend the Levant. In this regard, Saudi Arabia and Russia are among the conflict’s main protagonists. Saudi Arabia is one of the principal sources of political, military, and economic support for a number of armed opposition factions, including various radical Islamist currents, which have taken up arms against the Ba’athist regime.

Saudi Arabia views the conflict in Syria through the prism of geopolitics. As Iran’s most important ally, the uprising in Syria presented an opportunity to undermine Tehran’s influence in the Persian Gulf and greater Middle East. In doing so, the kingdom resorts to a sectarian invective characterized by an anti-Shi’ite discourse reflective of the hardline Salafist and Wahhabist ideologies promoted by its religious establishment domestically and internationally. Saudi Arabia is joined most prominently by Qatar and Turkey and, to different degrees, other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and Jordan in aiding and abetting the rival political and armed opposition currents that are struggling against the Ba’athist regime. The U.S. and other Western allies are also invested in both the armed and political opposition. And while Saudi Arabia and other patrons of the opposition have formally declared war against Daesh, their streams of support readily make their way into the hands of hardline Salafist and other armed Islamist extremists, the dominant insurgent cohort within the insurgency. Many of these factions maintain ideological and operational links to al-Qaeda’s Syria-based affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra and have achieved other levels of cooperation under the auspices of umbrella insurgent coalitions such as Jaish al-Fatah (Army of Conquest).

Russia, for its part, continues to provide the Ba’athist regime with a critical lifeline of support in the diplomatic, military, and economic realms. The latest displays of overt Russian military might in Syria are emblematic of Moscow’s determination to ensure that its interests in Syria are preserved. The recent displays of operational coordination between Russia and Iran in Syria and other theaters represent another critical facet of Russia’s involvement in Syria.

In many respects, the factors that have helped shape Russia’s approach toward Syria represent a carryover of the Cold War. The Soviet Union and Syria enjoyed friendly ties that spanned the diplomatic, military, economic, ideological, and social domains. The brand of secularism and socialism represented by Syrian-style Ba’athist ideology shared a great deal in common with Soviet-style socialism and command economy. While it may eventually adopt a flexible position toward al-Assad’s survival – indeed, Russia has issued a number of proposals to end the conflict, some of which have demonstrated a potentially flexible position toward the disposition of al-Assad – Russia at this juncture remains committed to the Ba’athist regime, in one form or another, a prospect that likely includes the continuation of al-Assad at the helm for the foreseeable future. This reality leaves it irreconcilable with the objectives pursued by Saudi Arabia. On the diplomatic front, Russia has attempted to outmaneuver the efforts of Saudi Arabia and other opponents of the Ba’athist regime by hosting its own diplomatic initiatives.

Much has been said of Russia’s military presence in Syria. Russia has maintained a modest naval refueling station in Syria’s port city of Tartus since the end of the Cold War. In a region dominated by pro-U.S. regimes, Syria represents a critical ally. But Russia’s continued support for al-Assad in particular and the Ba’athist regime more broadly is also rooted in deeper worries about the perceived intentions of its rivals the United States and its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) rivals.

In Russia’s view, the incremental expansion of NATO into its former sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union represents an affront to Russia’s sovereignty and an existential threat to its existence. Moscow’s intervention in Syria must also therefore be viewed through a wider geopolitical lens that is reflective of Russia’s attempt to reassert its perceived status as a global power. The prominent radical Islamist current within the broader insurgency, which includes a sizeable cohort of Russian citizens and others from across the former Soviet Union, is another factor of concern. Saudi Arabia’s track record of encouraging the spread of hardline Salafist and Wahabbist ideologies, including among Russian Muslims and others in the former Soviet Union, remains a point of contention in Saudi-Russo ties. The central role played by Saudi Arabia in supporting the mujahedeen struggle against the Soviet Union after it had invaded Afghanistan continues to color Russian perceptions of the kingdom. Consequently, the potential fall of the Ba’athist regime may serve as a springboard for insurrection in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Relatedly, Turkey’s actions in Syria have likewise raised consternation in Russia. Despite sharing close economic ties centered around energy and other major sectors – Turkey is the largest consumer of Russian natural gas after Germany – Russia worries that the Ba’athist regime’s demise would embolden an ascendant Turkey to project its authority further into Russia’s traditional sphere of influence in the Caucasus and former Soviet Central Asia, especially among the regime’s largely ethnic Turkic and Muslim populations. Many of the region’s ethnic Turkic populations share ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural ties with Turkey. The recent victory of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party in November’s Grand National Assembly elections has likely provided his government with the mandate it needs to press ahead with its agenda in Syria. In this context, the growing convergence of interests between Saudi Arabia and Turkey over Syria raises another set of alarm bells in Moscow. Saudi Arabia and Turkey have set aside their longstanding differences in order to more closely coordinate activities in support of the political and armed wings of the Syrian opposition.

Retaliatory Response

Saudi Arabia has initiated a retaliatory policy against Russia. The kingdom, alongside other benefactors of the armed opposition, has strongly condemned Moscow’s decision to launch air strikes in Syria. While not a reflection of official policy, the call by over 50 Saudi clerics associated with the domestic Saudi opposition for Arabs and Muslims to take up arms against Russia, as well as Iran and other supporters of the Ba’athist regime, is likely to resonate widely with a sizeable percentage of the Saudi population that views the conflict through a hardline sectarian framework analogous to what is advocated by Daesh and al-Qaeda. The statement by the Russian Orthodox Church describing Russia’s actions in Syria as a “holy war” has also inflamed tensions between Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Saudi Arabia is also reported to have increased its material support for the armed opposition, specifically in the forms of facilitating the transfer of U.S.-made BGM-71 TOW (Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided) anti-tank missiles provided by U.S. intelligence, to various armed factions. In operational terms, the introduction of the TOW systems helps to counter Syria’s largely Russian-origin heavy armor platforms and any future weapons systems supplied by Russia to the Ba’athist regime. Saudi Arabia has also been suspected of orchestrating numerous attacks targeting Russian interests across Syria, including operations launched by militants associated with Jaish al-Fateh and Jaish al-Islam (Army of Islam).

Riyadh is leveraging its economic influence to confront the Kremlin over Syria. There is speculation that Saudi Arabia is intent to keep oil prices low by way of boosting its overall production and incorporating price discounting in order to undermine rivals such as Russia that depend heavily on oil and other energy-generated revenues. In doing so, the kingdom is able to gain leverage in critical markets such as Europe and Asia at the expense of competitors such as Russia. Saudi Arabia resorted to similar measures during the Cold War to undermine the Soviet Union.

Notwithstanding the fluidity of the situation on the battlefield and in diplomatic circles, the Saudi-Russian rivalry over Syria will become increasingly relevant as the conflict continues to unfold.

Chris Zambelis is a senior analyst with Helios Global Inc., a risk management group based in the Washington, D.C.-area. He specializes in Middle East affairs. The opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of Helios Global, Inc.

This article is being published in affiliation with Gulf State Analytics